Luckily, Scholarly and Scientific dislikes rarely result in bodily assaults. Intellectual

assaults, on the other hand…..

A couple of weeks ago I was doing some searching in Google Scholar and by chance came across a paper with an interesting title and link to the full-text pdf. Being the inquisitive sort, I decided to take a look at the 2008 paper, written by a not insignificant scholar within his discipline- a critique of some highly cited papers on a set of concepts that have become increasingly central within the theoretical literature of Disaster Studies and Sciences. The paper is unpublished but can be found on a page of the author’s website (he even encourages responses if anyone feels he has made any factual errors). For a variety of reasons I will not specifically identify the author or paper…those with the curiosity and the time should be able to find it without too much difficulty.

To call the paper a “critique” is like calling the Inquisition an “investigation”. In fact, the paper can very well be described as a scholarly inquisition of four highly-cited academic papers, done with all of the energy and ferocity of a hungry lion chasing down a limping gazelle. Use of words and phrases such as “conflict of interest”, ” unscientific approaches and analyses”, and “sentences that demonstrate verbiage more than useful commentary” are not frequently encountered in scholarly reviews of other scholars’ work. It is also rare for scholarly works to be criticized almost line-by-line. As one of the papers placed on the chopping block is a bibliometric analysis by Janssen, Schoon, and Borner (2006), I take particular interest (Borner is a key figure in bibliometrics and the development of Knowledge Domain Visualization, and has collaborated with Dr. Chen, whose own work inspired my own).

Being that my undergraduate minor was philosophy, I am quite use to very detailed critiques of arguments and ideas, and strong debates, even when one actually agrees with a particular position being taken. The purpose is ultimately (in theory) to find the weaknesses in an argument which must be addressed, and if addressed satisfactorily, will make the argument stronger. If the weakness cannot be addressed satisfactorily, then the position must be abandoned. In reality, one learns that the nature and manner of criticism often reveals much about the position of the person offering the criticism. Some of the possibilities:

A) The critic comes from the same school of thought and agrees with the argument.

B) The critic comes from the same school of thought but disagrees with the argument.

C) The critic comes from another school of thought not fundamentally incompatible with the school of thought making the argument.

D) The critic comes from another school of thought fundamentally incompatible/opposed to the school of thought making the argument.

E) The critic personally has something to gain/lose from either supporting or opposing the argument, or personally likes/dislikes/despises the proponent of the argument.

If you combine motivations D and E, you now have a potential for manners and styles of criticism that are ferocious, unrelenting, and even nasty. Sometimes the disagreements even find their way into the public discourse, such as Noam Chomsky’s repeated criticisms of B.F. Skinner and behaviorism that first started with book reviews of Skinner’s work in the New York Times Review of Books.

So of course, the paper in question’s disdainful tone made me wonder if there isn’t an interesting story explaining the genesis of the paper. There probably is. There always is.

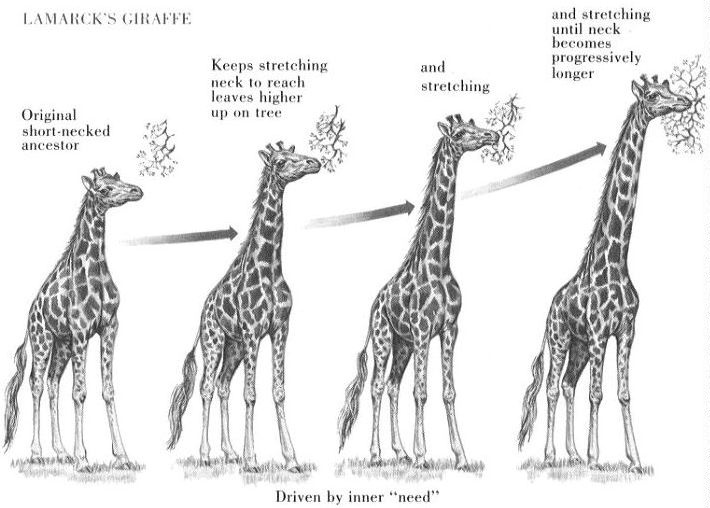

The simple fact is….and I hope this doesn’t come as a shock to anyone….please sit down if you still believe in Santa Clause, the Easter Bunny, and the wholly noble pursuit of knowledge……every scientist and scholar (and I am not excluded either) has a potentially serious, and possibly overlooked, conflict-of-interest: their own ego, needs, and desires. Scientists and scholars, particularly leading figures in fields, disciplines, and schools of thought, or those wishing to become leading figures, have deep, vested, interests in being mostly right. To admit, or to be shown to be wrong is to risk the loss of power, prestige, influence, income, etc. As Kuhn noted in his model of scientific progress, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, the nature of natural science is generally conservative and is loathe to enter a revolutionary phase until it has no other choice. Even at that point, many who hold to the status quo may still cling to the dying paradigm, for it is likely that no matter what they do, they will not be a part of the new scientific power structure. Some will go down with the ship while others secure an honored place in history. Darwin is remembered as a scientific and intellectual giant; Lemarck is remembered as a bit of a joke, and as the guy who “got it wrong.” His theory is frequently presented with the mandatory giraffe illustration (see below) to simplify his theory and maximize his “wrongness.”

This is how the history of science remembers the French biologist Lemarck. Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, was a contemporary of Lemarck and independently developed a very similar explanation for the evolution of species.

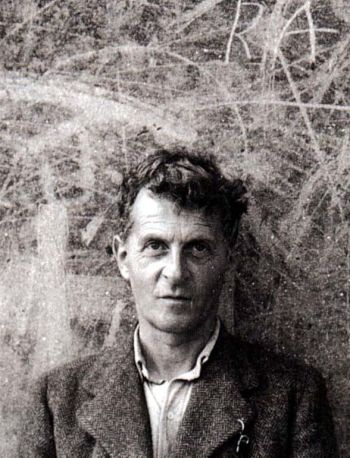

In the history of philosophy, there is only one philosopher known to have concluded that he “got it wrong”: Ludwig Wittgenstein. In his lifetime he published only one book, but was working on a second at the time of his death, which was translated and published two years later. The first presents one view of language and its relation to the world. The second contends that his view of language in the first book is wrong, and a new view is offered. This also leads to Wittgenstein’s distinction as the only philosopher known to have fathered two competing schools of thought, and he still holds a place as one of the more significant philosophers of the 20th Century.

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (1889-1951). One of my favorite philosophers. His only philosophical treatise published during his lifetime (in 1918) is presented as a series of logical propositions that begins with “1* The world is all that is the case.” Sixty-nine pages later it concludes with the final proposition: “7 What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” These lines are somewhat famous in the world of philosophy.

Off the top of my head, I cannot think of any similar examples from other disciplines. Many people know of Einstein’s famous quote, “God does not play dice with the universe.” What many may not know is the context of the quote, which reflected his negative view of quantum theory, which he never fully accepted, even when it was largely accepted by the rest of physics. But Einstein got it wrong- God does play dice with the universe. More importantly, some have expressed the opinion that had Einstein embraced quantum theory, he might have been the one theoretical physicist capable of finding an answer to the elusive problem of a unified field theory.

But the problem of personal motivation takes on importance for scholars and scientists for another reason: power, manipulation, and the possibility for abuse. This I learned from my time in psychology. In clinical psychology/psychiatry/psychotherapy, there is a tradition going back to at least Freud, that those who wish to be therapists must themselves undergo therapy. In part this is to create awareness of one’s own personal issues that can impair clinical judgements, and even harm clients, whether intentionally or accidentally. It is one of the only fields I know of that requires demonstrating such self-awareness….how many fields require the practitioner to ask following a bad outcome, “Did I in some way want this to happen, and in some way contribute to it happening?” Yet many fields and professions give power that can lead to manipulation and abuse in ways great and small. For the scientist and scholar, personal motivations and agendas can easily cloak themselves behind the supposedly unbiased, objective, pursuit of knowledge. Rationalists believed that the mind is the ultimate master of emotion. Science is usually imagined as a rational endeavor. The reality is that the mind all too easily becomes the blind servant to emotion (Schopenhauer referred to it as “The Will”, which is insatiable and unending in its wants, and it uses reason as a tool to achieve its wants). This is true regardless of whether you are a ditch digger or a Nobel Prize-winning physicist . If unrecognized, it can lead to questionable scholarship and science.

This brings me back to the critique in question. The author claims that his concerns are purely scientific. Are they? Besides the fact that feeling the need to point out the “scientific” nature of one’s own scathing critique of other scholars raises a red flag (if one is a scientist or a scholar, there really doesn’t seem to be a need to self-proclaim one’s work as being scientific or scholarly…unless one is actually saying something like “I am a real scientist, and I am far superior to these other bozos who only think they are scientists, and who are being cited much more frequently than my own work ), are there any other indications that the paper is less than objective?

Perhaps we should look at the truth-value, or accuracy, of the criticisms offered? This assumes that perfectly truthful statements cannot be used for self-serving purposes. That they can indeed be used for such purposes is exactly the problem. It is perhaps better to ask if the nature and manner of criticisms are legitimate, fair, customary, and/or consistent. Is there evidence of such failings? I believe there is. It is not customary in most fields to specifically single out four works (two by the same author) for microscopic scrutiny, and in a tone that borders on contemptuous. Even if one of the legitimate purposes is to support a claim that citation totals cannot be used to indicate the quality or importance of a work, the method employed cannot support such a claim, as it is selective not systematic. On the surface this would appear to contradict the stated scientific nature of the paper’s criticism. The method and manner of critique effectively implies, “I have shown that these four works are worthless crap and you shouldn’t pay attention to them. But the works of the other authors I cite in this paper are good and I have no criticisms of them.” Thus, the critique exceeds not only what is customary, but to discredit four works while implying they are the only four worth discrediting, also exceeds what would seem to be fair.

Even more importantly, can the paper itself meet the very standard of scholarship it applies to the works critiqued? If it cannot, then the standard applied is perhaps excessive, or it is simply the case that the author’s very own paper is of equally poor quality as the works criticized. In the paper’s criticisms, much is made of the authors’ lack of knowledge of the literature of the field, documented with numerous examples. The author himself, however, fails to cite a single author or paper on the topic of citation analysis when criticizing the 2006 Janssen et al. paper, or presenting his own thoughts regarding the use of citation analysis. In 2008 there was a large and substantial literature in existence on the subject that had been developing for nearly 40 years. Some specific criticisms offered also indicate a lack of awareness of not only the literature, but of the very nature of the method used in the Janssen paper. The author is not only doing what he accuses the other scholars of doing, he is actually doing it to a greater degree by completely ignoring the body of work within another discipline.

Thus, there seems to be more going on in this paper than what is claimed. What exactly is going on really doesn’t matter…the author might simply have been having a really bad month….maybe he wanted to call attention to authors and works more closely aligned to his views that he felt were being neglected (though the very history of science is filled with good papers and authors that ultimately get lost within the immense volume of work constantly produced, or they fail to get the credit they perhaps “deserve” for ideas that another author becomes more widely known for).

The fact that there is likely a very loudly expressed unspoken agenda to this paper is what matters. I consider this a form of deception. It is dishonest.

I hope there is a lesson in this. Socrates’ words from long ago apply just as much, if not more, to scholars and scientists as they do to everyone else: “Know thyself.” We must try to be be clear and careful about the masters, internal and external, we serve in the name of science and knowledge.

If nothing else, it should serve as a warning to scholars in this digital age to perhaps think twice before putting unpublished papers on your website. You never know when some upstart researcher, motivated by an underlying need to confront arrogant authority figures as well as by the need to establish his/her own reputation, will discover something you might have forgotten ever writing, and turn it into the subject of a blog posting.