Home » Posts tagged 'disaster theory'

Tag Archives: disaster theory

Moral Luck in Emergency and Disaster Management

The philosopher Thomas Nagel–when bad things happen, someone is probably going to get blamed, and a whole lot of other people should breathe a big sigh of relief and thank their lucky moral stars it wasn’t them…

Although he did not coin the term, Thomas Nagel’s 1979 paper on the problem of moral luck is considered a classic work of modern Ethics.

For the benefit of anyone that is unfamiliar with the idea of moral luck, or for those who think they know but who are actually thinking about moral hazard (which is something completely different), I will explain the problem. A foundation of most ethical systems is that we can only hold someone morally blameworthy/praiseworthy for actions and their consequences to the extent that the actions/consequences are voluntary/controllable. Someone who does something against their will, or who lacks control over the outcome of their actions, is not held morally liable, or is judged less liable. We also expect that if different people perform the exact same blameworthy/praiseworthy action, all will share the same amount of moral liability. But this is not the case. The same action can and does result in individuals being held morally responsible unequally.

Imagine you are driving down a street and are typing a text message on your IPhone (don’t tell me you have never done such a thing….). In the split second that you are not paying attention to the road, a dog whose owner has briefly taken off its leash is sitting by the curb on your side of the street. The dog suddenly sees a squirrel on the other side of the street. Just as your eyes return to the road, the dog decides to chase the squirrel and darts in front of your car. You instinctively swerve to avoid the dog, hit the curb and go up on the sidewalk, where your car hits and kills the dog’s owner. Other people, yourself, and likely the law, will judge you morally responsible in the death, though unintentional, of the dog’s owner. But in the chain of small actions that will ultimately lead to the dog owner’s death, many of them are outside your control. One small change in those factors and the outcome is different. If you had been at that very location either a few seconds earlier or just a second later….if the dog’s owner had not taken off the leash….if the owner had been standing 4 feet to the left….no moral judgments, or much lesser judgments, of your actions would be made.

Now let’s say that this occasion was the first and only time you had ever tried to text and drive. That same day, 25,000 people around the nation sent a text while driving, and you are the only person whose action results in someone’s death. Of those 25,000 people, let us say 5,000 of them text and drive every day. 100 of them have had minor traffic accidents while texting and driving. But you are still the only person among 25,000 people whose action results in the death of another person. Everyone is performing the same blameworthy action. The actions are the same, but the moral consequences to the actors can be very different. You have just encountered moral bad luck.

Moral luck can also result in morally repugnant actions being judged less harshly. As a frequent Investigation Discovery viewer, I have noticed cases where an individual has attempted to kill someone in some particularly vicious, and sadistic way (shoots, stabs, and then throws the body in a wood chipper…). By some improbable circumstance the victim survives (electrical short causes wood chipper not to start…). Because murder is held to be a greater moral offense than the act of attempted murder, an individual we might think would be sentenced to life imprisonment without parole is sentenced to a less harsh sentence.

Moral luck calls into question the consistency and fairness of many of our moral and ethical evaluations. Many of the events that we may use as evidence of the moral failing/superiority of an individual’s character, are to some degree the result of chance. Any system of ethical conduct that takes into account the degree to which action is voluntary or not must account for the problem of moral luck. Nagel himself did not have an answer. Other philosophers have attempted to find one, but so far none appear to be completely satisfactory.

MORAL LUCK AS A PROBLEM FOR EMERGENCY AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT

A tale of three FEMA Directors and their reputations. One is held in almost mythic regard. One became the brunt of many jokes, and possibly became the joke. The third started strong but cracks may be showing. Are they truly as good or as bad as we think, or are our evaluations obscured by the problem of moral luck? If Katrina had instead happened early in the tenures of Witt or Fugate, and Brown’s tenure was absent any catastrophic disaster, might the reputations of the three be quite different? Brown would likely say an emphatic “Yes!”

If you have not yet began to intuit the connection between moral luck and EDM, let us look at the problem from a different perspective. Instead of talking about ethics and moral judgement (which often leads people to wrongly think we are somehow talking about religion) let us say that we are essentially dealing with a problem of assigning responsibility. When good or bad things happen that can be attributed to an individual’s actions, how much of what happened is due to a specific quality of the person involved, and how much of the outcome is the result is due to the situation itself? If an accident occurs because of an error that I can hold someone responsible for, if I find that the same error could have occurred no matter who was placed in the situation, then I might conclude that the accident did not happen because of the specific person involved: anyone else could have made the same mistake but this person had the bad luck to be the one. It also suggests that there are changes to systems, environment, etc., that could reduce the chance of the same error being made again. The person is responsible but they are not to blame.

If you think this discussion is purely academic, think again. In some countries like Italy, responsibility, liability, and blame are not so differentiated. Air traffic controllers have gone to prison, not for negligence or some intentional act causing an airline crash: they have made human errors in the performance of their job that could have been made by any other controller in the same situation. I wonder if our own society is becoming increasingly blame-oriented.

Despite the progress made within the field of EDM, our methods for evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of emergency and disaster policy and programs are…let us be honest…crude at best. I am periodically reminded of this fact when reading “Best Practice” articles. It frequently appears that the key criteria for something to earn a best practice label is whether a submission meets the “sounds like a good idea” and “does it make us look like we are doing something” tests. One may also find that effectiveness of a policy, procedure, or program, is evidenced primarily by the fact that nothing really bad has happened since. As simplistic and silly as that may sound, the pattern of EDM policy developments and directions and over the last 30 years suggests this is largely how success and failure is measured. We assume the things we do are working until there is a disaster that we have difficulty handling. Answers (and probably a few heads) will be demanded. Often the very things we thought or were told were working fine will be judged as not working, or in fact are part of the problem. People will be blamed and replaced. Policies and procedures are likely to undergo substantial change. We will call the results “an improvement” …until the next catastrophe.

Some solutions to the problem are relatively easy to find. Moral luck appears to be less of a problem in truly “professional” fields like medicine. Even the best of doctors will have bad patient outcomes, and it isn’t automatically assumed that the doctor is to blame. A physician is expected to fully understand the expectations, standards, methods, outcomes, and conduct that must be followed within the profession. They are ingrained into the physician, both explicitly and implicitly, through their education and training. Ongoing research and data collection allows the profession to evaluate and re-evaluate treatments and procedures, as well as establishing baselines to which a particular physician or hospital’s performance can be compared. By comparison, emergency management in the US has only recently managed to produce a basic definition and some general principles.

There is a very long way to go….

The Necessity of Change, “Forgotten” Cities, and the Conceptualization of Disaster Resilience: Galveston, TX

Footage shot covertly by one of Edison’s assistants sent to Galveston to try to capture the aftermath of the 1900 hurricane using the new technology of moving pictures. This is among the oldest motion picture footage known to exist. More of the Galveston footage can be seen on the Texas Archives website- http://www.texasarchive.org/library/index.php/Category:Galveston_Hurricane_of_1900

1900 Hurricane Damage Survey (http://www.gthcenter.org/exhibits/storms/1900/maps/index.html)

Monument on the Galveston seawall in memory of the 6,000-8,000 victims of the 1900 Hurricane, which remains the single deadliest natural disaster (excluding the 1918-20 pandemic) in US history (photo courtesy of the author). Considering the city lost approximately 15% of its population, it displayed remarkable resiliency in the face of such catastrophe. Construction of the first section of the 10 mile seawall was completed in 1904; and from 1903-1911, the grade of 500 city blocks was raised up to 16 feet. These feats were accomplished long before the days of FEMA and federal disaster assistance. But the city still began a slow demise. Was the 1900 Hurricane responsible, or was the demise inevitable sooner or later?

“Time the destroyer is time the preserver”

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

Driving home from a hockey game last night in Dallas, I shared with the friend that accompanied me, some of the ideas I was working on for today’s post. She pointed out that I am unlikely to ever be mistaken for the bluebird of happiness. Here is the evidence she based her observation on:

Sometimes I think it is one of the cruel jokes of the universe that humans would develop the tendency to often covet most the things that we cannot have. We often dream of things eternal and everlasting. We find comfort in the familiar and seek stability. Unfortunately, we are bound to a universe with time and space woven into its fabric. The necessity of change becomes an essential property of every particle, atom, molecule, element, organism, and system under the sun. Should change ever come to an end in our universe, at that moment time also ends, and the eternal, everlasting Utopic universe of our dreams is revealed to be neither Utopic nor dream-like: it is a place motionless, frozen, and hidden in impenetrable darkness. The perpetuity and relentlessness of change and all that entails (creation, destruction, birth, decay, death, beginnings, endings, and transformations) may not sound very comforting to many (most?)…but the alternative is much worse.

I would agree that such thoughts will probably keep me out of the running for Optimist of the Year. Unfortunately the mechanics of our universe are not dependent on whether we find those mechanics comforting or frightening. Ideas such as societal “progress” over time; or the idea that man can conquer nature through intellect and technology, are both fairly recent, as well as Western inventions. As a student of philosophy, particularly Eastern (primarily Buddhist and Taoist) thought, the Oriental view places no faith in humankind’s ability to conquer nature. In fact, the attempt to do so is in itself a self-deluded folly, and one source of future failure, unhappiness, and misery in life.

In both Taoism and Buddhism, our own concepts, desires, and “needs” distort the world and its processes we see. Only when we stop fighting against the underlying “energy flow” or “nature” of the universe, which in Taoism is “the Tao” (which has existed far longer and is infinitely stronger than us) can we hope to live in harmony with that universe (but it is not a static, unchanging, harmony…as the universe changes we too must adapt to remain within, as I believe Wittgenstein called it, the flow of the river of life). If we swim against the current, we will drown. In Buddhism, the goal of the Buddhist mind is to attain a mind that is frequently described as a perfect, unblemished, mirror, reflecting the world exactly as it is, free of all distortion. To see the world as it is, not as we want it to be, releases us of much frustration, anger, and disappointment.

I bring these ideas up because, when we talk about disaster resilience, community resilience, national resilience, etc., disaster resilience is described as if it is a were a relatively stable, unidirectional (will increase with the proper effort), property of a community. If one believes some of the radical geographers, if all disasters are the product of man, then man has the ability to stop disasters. If only we design the proper programs/interventions, we can increase a community’s resiliency and expect it to be maintained near this new level. I am not so sure this is the correct view. I think we should not be surprised in the future (assuming we have managed to create an assessment instrument that provides us a valid, reliable, and sensitive measure of disaster resiliency) if we discover that the measured resiliency of neighborhoods, communities, cities, etc., fluctuates significantly (both up and down) over time, and may even appear to change independently of our interventions. We may find that some communities, regardless of our efforts, become steadily less resilient over time, as if the community was actively defying our attempts to make it more resilient to disaster. This may sound strange. Perhaps what I mean is better expressed by saying the community appears as if it were actively refusing, or unable, to adapt.

By the same token we may find communities we believe to be quite resilient in the aftermath of one or more disasters, only to later see the community flounder unexpectedly, failing to recover following the same type of disaster it had previously already exhibited sufficient adaptive capacity.

In the history of the city of Galveston, we see these contradictions and paradoxes play out, possibly showing us the problem of framing disaster resiliency within the larger context of community resiliency. In 1900, Galveston was in its prosperous “Golden Age.” Its place as Texas’ primary port made it a key center of commerce and wealth. In the aftermath of September 8, 1900’s devastation, there is no evidence that its citizens saw the event as either the end of Galveston or of its commercial importance. The city displayed a level of resiliency that is hard to believe in the face of the loss of approximately 15% of its population, 3,000 destroyed structures, and damage to approximately 95% of all buildings. Not only was reconstruction started, but the massive engineering and construction marvel that is the 10 mile long seawall and the physical grade raising of parts of the island, was undertaken. There was no FEMA. There was no centralized federal assistance to rebuild. There was the state, and there was the city and county of Galveston. This was Galveston’s exercise of the will and resources to reconstruct (This is another paradox of disaster resiliency..today such rebuilding is now impossible as our society has become increasingly specialized, labor divided, and regulated. Communities/neighborhoods and those that reside within them have become increasingly isolated and disconnected. In a very real sense the adaptive capacity of communities and individuals was greater in 1900 than it is in 2013).

However, even as Galveston rebuilt, economic forces were taking shape that the city would not be able to withstand. Even had the city had the foresight to have been better prepared for the 1900 Hurricane (the idea of the seawall had been first proposed between 1886 and 1890 following the destruction and abandonment of Indianola, TX following an 1886 storm), it is questionable such actions would have prevented the future demise of the city. What the Hurricane did possibly hasten (by maybe a couple of years at most) was shipping companies’ and manufacturers’ questioning of Galveston as Texas’ primary port. As a barrier island, however, one could argue that Galveston should never have been the primary port of Texas. With the discovery of oil at Spindletop, near Beaumont in 1901, the nearby city of Houston would eventually take Galveston’s place as Texas’ key center of commerce and wealth.

With the decline of the city as a major port, Galveston’s economy eventually shifted to one reliant on illegal gambling operations and tourism (the period of “The Free State of Galveston”). Once law enforcement efforts in the 1950’s took away this source of revenue, the city’s only other significant source of revenue, tourism, also declined. Over time, the loss of revenue that once offset an eroding tax base combined with the failure to find other revenue solutions. The city was left with insufficient revenue to support its basic infrastructure, and decline and decay followed.

Despite its previous ability to bounce back from the worst natural disaster in U.S. history, Hurricane Ike in 2008 struck a city that was only a shadow of its former self…its disaster vulnerability was a reflection of its terminal economic decline. One could argue that Ike simply put a final exclamation point and established a time of death for a city that was dying long before Ike ever formed.

Galveston now sits on MIT’s list of Forgotten Cities (http://www.policylink.org/atf/cf/%7B97c6d565-bb43-406d-a6d5-eca3bbf35af0%7D/VOICES-FORGOTTENCITIES_FINAL.PDF): mid-sized cities that are effectively dead economically, decaying, and socially in disrepair. The state of these cities does not have to be permanent. With investment, re-development, creativity, and economic diversification, many of these cities, if not all, may one day begin a new cycle of growth…..that will eventually involve future periods of decline and decay, rise and fall. All cities, or communities within cities, must cope, adapt, or die in the face of the ebb and flow of their environment.

Is New Orleans fated to become another “forgotten city”? At what cost and in what form is it worth saving?

So what is the lesson here? Perhaps it is that we need to begin realizing that at times it is more prudent to adapt rather than try to stop change when that change may be unavoidable. Sometimes disasters may be an important part of telling us that some form of change is necessary…and the change needed may be something different than a new seawall. If we only focus on recovering, rebuilding, and mitigating disaster, we may miss the larger picture of what the disaster is really telling us. Unfortunately, we may not like what we hear, and chose to hear something else.

When I look at New Orleans, or even San Francisco, as much as these cities are loved (New Orleans is one of my favorite cities in the world…its own economic decline began long before Katrina) and we wish they could go on forever as we remember them: they may be cities that all of the improvements we can think of, and all the riches we could invest to increase their disaster resiliency as they currently stand, might do little to save them from their ultimate fate.

Instead of trying so hard to save cities/communities as they once were, and perhaps can never be again, we might be smarter to plan how to maximize what they could become if they are willing to accept and adapt.

All things will change. No one said we had to like it.

Joining the Bandwagon: The American Red Cross Embraces the “Disaster Cycle” and Resilience

Though I may gaze upon the Red Cross, as an organization, with some degree of amusement and cynicism, it does not lessen my support (best provided from the safety of a volunteer position) of its humanitarian mission….

If you haven’t heard, the American Red Cross is currently “re-engineering” its Disaster Services. This initiative should not be confused with the national “restructuring” that occurred throughout 2011 (in Texas, this restructuring consolidated the 8-10 existing Texas ARC Regions into four regions, each one larger than many states…on the very day the change took effect, mother nature celebrated the change with the start of the worst wildfires in Texas’ history). For some staff members, who have once again seen their job eliminated or merged into another position, resulting once again in the need to re-apply for their job, the end result of the two efforts has been similar. With all of the recent restructuring/reorganizing/re-engineering, who could blame staff members for wondering if they should just plan on re-applying for their job every two years…

In the brave new world of ARC Disaster Services, organization of services will be based upon the completely useful, but totally artificial, concept of the “disaster cycle.” So there will be Preparedness, Response, and Recovery functions, plus many of the old functions (logistics…operations management) that don’t fit so neatly under just one of the three phases, all packaged under the new title of Disaster Cycle Management. I did not realize there was a critical shortage of terminology in the field. Emergency Management, Comprehensive Emergency Management, Integrated Emergency Management, Integrated Disaster Risk Management, Disaster Management, Disaster Risk Reduction, Disaster Services, and other terms weren’t sufficient? Now Disaster Cycle Management arrives to crash the party. The term makes me think of disaster management and washing machines. Needlessly coining new terminology is almost more than I can take, but….I think I can live with it.

Community resilience is also making its way into the language of ARC, and the staff member whom I serve as a Volunteer Partner, will soon sit in the newly created position of Regional Manager, Individual and Community Preparedness and Resilience. It worries me to see the concept of resilience appearing as a form of job title, when neither researchers nor practitioners are quite sure exactly what resilience is or is not, and how can it be quantified meaningfully. And operationalization and quantification of resilience as a performance goal is what I fear ARC will do. ARC likes to quantify and demystify the abstract…disaster magnitudes, for example, are categorized into tiers based on ARC financial expenditures for the disaster. This makes sense.

Sometimes, however, attempts at quantification to improve performance can interfere with the performance it was meant to improve. In ARC Disaster Assessment, for example, one particular measure of good performance has been the percentage difference between our PDA (preliminary damage assessment) and the final damage totals (what we call the Detailed Damage Assessment). Discrepancies exceeding a particular threshold (I seem to recall it being somewhere around 2-5%) is unacceptable.

Adherence to this goal is so ingrained into DA Managers, that I have seen how concerned people appear to become if new information from the field results in substantial increases to the PDA total. Such was the case during the 2011 Texas wildfires, when a DA field team spoke to a member of one town’s city council, which lead to the discovery of 80-100 destroyed homes that neither the city, county, state, nor local media were reporting. As the person who was checking and rechecking damage estimates several times a day, as well as locating potential damage locations for DA teams to check, I could almost hear someone above me in the hierarchy asking, “Well…how do you miss 80-100 homes in your PDA????” It really isn’t that difficult when you have multiple, rapidly changing, wildfires across something like 10,000 square miles. One could even point out that wildfires (and perhaps river flooding as well) are, almost by nature, an expanding, evolving, type of disaster unlike the “over-and-done-with” destruction of most earthquakes, hurricanes and tornadoes.

Last year I also had a heated argument with a DA Manager during the April DFW tornado outbreak. As I was unable to serve as DA Manager for the entire operation, I was asked to serve in that capacity, and assist in planning and maintaining situation awareness until the manager arrived later in the evening. I would then hand over to him and he could hit the ground running. I had spent the day of the outbreak, and most of the night, gathering damage reports from local media sources, confirming, and mapping known areas of damage, with the expectation DA teams would be going into the field first thing in the morning. I discovered the next morning that this did not happen. The DA Manager told me damage estimates from city and county officials are not acceptable sources for PDA damage numbers–they must come from DA field teams. He preferred to spend nearly two days having DA teams go out to do a PDA survey, even when the general boundaries of the damage area were known. He would then have those same teams go back to the same areas to begin the detailed assessment. This makes little sense to me, as it wastes our most valuable resource: the time of the volunteers. The entirety of the DDA could have been completed in 1-3 days, depending on how many teams were assigned. The sooner the DDA is completed, the sooner the client caseworkers will have the information they need to assist disaster victims, and the sooner the damage assessment side of the operation can wrap-up and go home.

That is when I learned to tell myself, “However the Manager wants it done is the way it is going to get done.”

Of course, when damage is spread across vast distances, or information about possible damage locations and severity is lacking, then good PDA and needs assessment methodology is essential (and which there does not seem to be much written about–a side project I may undertake when I start a PhD program is to work on investigating the accuracy of different geographic sampling methods in estimating needs and damages in large-scale disasters). The PDA is important, as these initial estimates will be used to scale the ARC response…though it is not the only information used. In terms of process, a PDA/DDA percent discrepancy isn’t nearly as important as whether it adversely affected ARC response; what was the cause (or causes) of the discrepancy; and whether or not, or to what extent, the cause of the discrepancy is a DA performance failure that can and should be corrected.

A Preliminary Damage Assessment (in terms of ARC) is supposed to be exactly that….PRELIMINARY–it may change..it probably will change….that is the nature and the fog of disaster. Whether it is damage assessments or resiliency indicators, when we are not careful, we unwittingly create systems that lead staff to serve not the actual process for which they are responsible, but instead some possibly arbitrary, or poorly constructed, marker of performance of the process.

In the case of community resilience, if ARC does decide to create performance measures, I do hope someone checks that whatever measures are chosen actually do correlate to some degree with measures of community disaster recovery and long-term risk reduction.

The Structure of Science Part I: A Most Curious Resemblance

Map of science based on the 2011 revised Web of Science categories in Leydesdorff, Carley, and Rafols (2013 in press) paper…..

Here is Leydesdorff, Rafols, and Chen’s updated 2013 journal-level map of science based on citing patterns among 10,675 journals indexed in Web of Science, as visualized in VOS Viewer. This map can be accessed at http://www.leydesdorff.net/journals11/. Does the structure of these networks look familiar to anyone?

I was originally planning to write about some interesting work being done by several information science researchers, including Loet Leydesdorff, Ismael Rafols, Chaomei Chen, and Alan Porter.

Their work improves on earlier work by Vargas-Quesada, De-Moya-Anegón, Chinchilla-Rodríguez, and González-Molina (2006), as well as others, to map the entire intellectual domain of science. The recent work involves creating overlays that can be combined with base structural maps of science derived from citation patterns within Web of Science-indexed journals. The overlays allow the output of a particular author, journal, institution, or field, to be visualized within the entire domain of science. These base maps, one of which is shown above, might help provide secondary confirmation of the structures I have found in my co-citation networks.

So, I was preparing images of the base maps and marking where different disaster-related journals referenced in my networks were located within. Then I noticed something. I had seen the structure of the base map before.

With my original background in neuropsychology, I have spent a lot of time looking at images of the human brain (and in one undergraduate course was tested on neuroanatomy using actual human brain sections the instructor kept in a large glass jar of formaldehyde in his office…..). The structure of science looks remarkably similar to a cerebral hemisphere seen from the side (lateral view). Even the way the major disciplines cluster along the outside of the network, with the curve creating an interior space, is similar to the curve of the temporal lobe and the relationship between gray and white matter:

Right cerebral hemisphere of the human brain. See a similarity between this and the network of science?

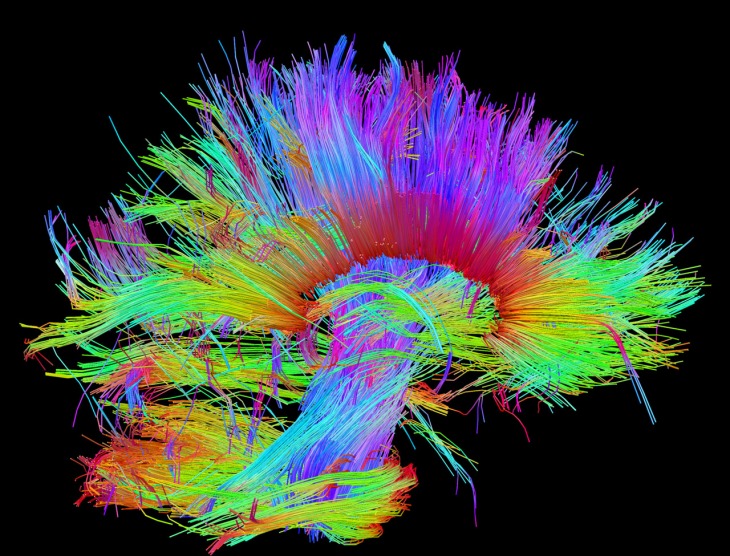

Sagittal section through the right cerebral hemisphere showing the brains thin outer neocortex (gray matter) and the immense number of axon bundles below the neocortex (white matter) that connect these neurons to others throughout the brain and nervous system.

The resemblance was so peculiar that I emailed Dr. Leydesdorff, who is in Amsterdam, to ask if anyone had noticed the similarity before. He actually replied back rather quickly that he had not noticed it before but that yes, the similarity was striking. Whether there is any significance to the similarity, he could not say one way or another. I can only speculate that if the structural similarity can not be shown to be coincidental or arbitrary, then it suggests there is something necessary about that structure that makes it desirable to have, for both brains and scientific knowledge domains. But the idea that the structure of knowledge somehow echoes the structure of our own brain is a very odd idea indeed!

Here are some additional images of neural pathways and networks that have been produced by the Human Connectome Project, which seeks to completely map all of the brain’s neural pathways and connections–a definitive wiring diagram for the human brain.

Perhaps someone else sees the similarity I do between these images and the network of science…..

Looking again at the right cerebral hemisphere. This Human Connectome Project image shows major neural pathways that connect the brainstem and midbrain (long bluish and purplish vertical fibers) to the pontine & cerebellar areas (yellow and orangish fibers that wrap around the base to the lower left), and cerebral cortex and neocortex (multicolored fibers that fan out from both the upper brainstem pathway and from around the red-ringed elliptical space, which marks the location of the thalamus and hypothalamus). Frontal lobe would be to the right, and occipital lobe to the left.

In Part II, I will return to my original intention of discussing the base maps of science in relation to my own attempts to map the structure of Disaster Studies and Sciences.

The Myth of the “Myth” of Natural Disasters and the Unspoken Disaster Taboo

The mysterious Dr. Ilan Kelman. Should we ever meet at a conference I think he will likely shake my hand…so long as he can’t quite put a finger on why my name sounds so familiar….

The great English philosopher George Berkeley once asked: if a hurricane causes a tree to fall in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it still make a sound? Many recent disaster researchers would reply that they have no idea if the tree made a sound, but they do know that the hurricane wasn’t a natural disaster if no one is around.

Ok, so maybe Berkeley never asked that exact question. Had he asked the question, and had there been any disaster researchers around at the time, I am certain he would have received such an answer. In my view, it has almost become cliche now to state, in some form or fashion, that without humans, there are no disasters. Authors differ not only in how this idea/argument is expressed, but also in how far they are willing to take the idea. Some authors have taken the idea further than others. Mileti, for example, in Disasters by Design, presents natural disasters as a result of the interaction between three systems: earth, human, and constructed environment. Other authors have gone much further, and have asserted that there are no “natural” disasters: all disasters are the result of human action.

There are many examples of this view, such as the UNISDR, or this 2010 Bankoff article that presents the term “natural disaster” as a form of…and I hate having to use the term….discourse. In Bankoff’s view, natural disasters are a convenient way for avoiding human responsibility, and closely tied to colonialism, development, and aid.

A personal favorite of this blog, Dr. Ilan Kelman is another such author. For a second time since starting the blog, I have accidentally stumbled upon one of his unpublished papers, where he not only asserts that there are no natural disasters; there are no natural hazards, either. He also reviews some of the key literature in the evolution of the “un-natural” natural disaster perspective. His general argument is that hazards are simply our interpretation of necessary natural processes, and it is our own choices that makes them hazards and leads to disasters. According to Kelman, should a gamma-ray burst roast Earth tomorrow, it apparently will be our own (and I note he particularly targets “the rich”) fault that we didn’t invest enough to prevent gamma ray bursts from turning the earth into a planetary BBQ. And in a style I am beginning to think is his trademark, Kelman proclaims after presenting several global catastrophe scenarios: “A full inventory and scientific analysis of these scenarios might provide some exceptions for the claims in this document that neither natural disasters nor natural hazards exist. “

Our good friend the earth-cooking gamma ray burst is back…Kelman says you can blame society if one should ever turn the human race into the charcoal briquette race. Maybe you agree with his point of view. I don’t.

The notion of the “un-natural” disaster has now been parroted by enough authors as if it were fact, to make me suspicious that it might be something other than a well-reasoned, logical, conclusion. Perhaps it is really a symbol, a slogan, a mantra….even….and once again I am sorry to use the term…a discourse.

Ideas are like jokes: you can take them too far. A good comic knows how far he can push the limits of a joke before he loses the audience. A bad comic crosses the line and then sight-sees awhile, oblivious to the fact that he is simply no longer funny. Likewise, in the land of ideas, a good thinker knows that there is one town no good idea goes: Absurdia. I think Kelman and perhaps other authors have gone too far, confused symbolic meaning with literal meaning, and have taken up residence in Absurdia.

What do I mean by saying that they have confused the symbolic and the literal? I mean that when authors speak of “un-natural” disasters, they are not attempting a systematic and logical analysis of “natural” disasters in order to clarify the concept of disaster at the conceptual/theoretical level. For example, I have yet to find an author who examines what is meant by the term “natural”, including how do we determine which human actions are natural and which are unnatural; or an author who addresses the fundamental question of whether it is correct to limit disasters to events involving humans: would other organisms perceive certain events as disaster-like if they had sufficient intellectual/emotional/linguistic ability, and would we perceive what happened to those same organisms as disasters? If human presence/action is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for disasters, then this should inform our conception of what is a natural or “un-natural” disaster.

Are disasters only applicable to human events? If we were one day to discover remnants of a long extinct alien civilization on another world, would the term “disaster” be one of the possible terms to describe what happened? Might the alien civilization have used a word in their own language with a similar meaning?

No, these writers serve another purpose, one with both positive and negative implications. On the positive side, the concept of the unnatural disaster is a way to teach/inform/remind people that human decisions play an important role in disaster processes. I think, however, humans throughout history have understood much better than many of these authors credit, the relationship between human actions and disasters, within the limits of their knowledge of the world. The human brain in 2013 is no different in its intellectual abilities than the brain of 2000 B.C.E. . Humans do not have to know the scientific explanations behind many geophysical events in order to learn and remember extreme events and their consequences upon humans, leading to attempts to prevent their re-occurrence. Some of these early prohibitions designed to prevent disasters may have been couched in the language of myth and religion, but it does not change the fact that it is a way to prevent human actions resulting in disastrous consequences.

On the negative side (at least in my view) is that you may begin to believe that the concept is not just a useful teaching device, it is also literally true. Human society is the cause of all disasters, and without humans there are no disasters. And here the idea of the unnatural disaster begins to serve a deeper ideological position. The position is what McEntire (2004) in a paper on theories of disaster and development refers to as the “radical thesis”, based in Marxist theory, that sees disasters as the result of economic and social inequities. Within this view, a global reduction in disasters requires elimination of these inequities and social injustices, which includes poverty and the development gap between richest and poorest nations. Social vulnerability and its reduction takes precedence above all else. What is sometimes missed in the discussion, as pointed out by Cardona (2003), is that social vulnerability to disasters is not really a specific vulnerability to disasters. The factors that frequently define the term (poverty, race, gender, etc.) make individuals more vulnerable and less able to recover from a broad spectrum of events, whether the event be related to crime, physical illness, mental illness, disaster, etc. The socially vulnerable are simply more vulnerable….period.

The reason this concerns me is because ideological positions are frequently based upon internally consistent, closed, systems of great explanatory power at the level of theory, but far less power to produce success when applied in practice. Public Administration authors, like Drucker (1980), have pointed out that an important reason for the failure of government programs and interventions is the all too frequent reliance on ideological/dogmatic ideas rather than empirical results. As the systems the positions are based upon are closed, failures can be explained away within the system rather than being taken as evidence there is something wrong with the system itself. As such, they often defy philosophical, scientific, or empirical arguments.

It is not only convenient but even necessary for the radical perspective to assert that all disasters are the result of human action, and therefore all disasters are preventable through human action. As a result, authors like Kelman find themselves trapped making arguments with absurd destinations, such as blaming society should we be destroyed by gamma ray bursts. There is unlikely any evidence or level of absurdity that one could present that would persuade Kelman he has taken a wrong-headed direction, as this would ultimately undermine the underlying radical thesis.

If these were the only problems in asserting the myth of the natural disaster, we would be left with an interesting but largely inconsequential academic debate. Unfortunately, for all of the radical thesis’ interest in development, sustainability, and reduction of inequity in the name of disaster reduction, they are as silent as much of the rest of the disaster community in addressing what almost seems a taboo subject: managing overpopulation and over-consumption (Smith, 1993). I find this particularly odd, as you would think that a group of thinkers so devoted to identifying the root causes of disasters, as the radical thesis proponents are, might be concerned about these issues. Particularly as history seems to tell us that as developing countries progress, their development will for a time paradoxically increase their population even more, as lifespans increase, fewer die by disease and disaster, etc. Their levels of consumption will also grow with development, and we so far have very little evidence of countries voluntarily curtailing their industrial growth, development, and consumption to ensure that resources will be available for other countries to develop. Everyone may say they hate the West and its values, but it seems everyone wants to equal its economic and industrial power. Unfortunately, the world cannot long sustain the continued industrial growth of the major world powers that already exist. Will any country say: “We will curtail (or even contract) our own growth for the good of humanity?”

By 2050 the human population is expected to be near or exceed 10 billion, with most of it in the developing or near-developed world. The UN anticipates the world population to peak around 10-11 billion, before stabilizing then declining . At the same time, countries like China, India, and Indonesia will continue their industrial development, demanding more and more resources to fuel their growth, with other countries waiting to follow in their footsteps. Although there are optimists who suggest that the earth’s carrying capacity could be as high as 40 billion, it seems most scientists believe that we are already past what is sustainable in terms of population and economic growth. According to The Limits of Growth and its updated results, human civilization appears to continue its advance towards some form of systemic collapse, whether by mid-century or later.

It took from the beginning of homo sapiens first appearance on earth until 1804 (55,000 years give or take a few) for the world’s population to reach 1 billion. In 2011 it reached 7 billion.

(World Population Clock: http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/#milestones)

As the Final World War begins, some very astute radical geographers and sociologists consider the possibility that it might have been a mistake to concentrate on disaster reduction through international development while ignoring overpopulation and over-consumption. They also take a moment to consider the positive side of the apocolypse: the gap between richest and poorest countries should narrow remarkably over the next several hours; and we can now all stop worrying about the future effects of global climate change…

Seen in this light, irrespective of climate change, we should not be surprised to see in coming years growing instability and rising disaster costs throughout the world. Seen from a systems perspective, these events will not be the problem itself, though based on current scholarship, we are likely to treat future disasters as such, or attribute the symptom to a closely related issue, but one that is still only a symptom: climate change. The reality may be far worse: the system of human civilization itself is becoming more and more unstable as population and consumption grows, with disasters becoming more frequent and/or larger as the system becomes increasingly unable to find lasting stability. When the system finally begins a global cascade failure, we will likely not recognize it as such when it begins. As the failure spirals out of our control, we might begin to recognize it for what it is: part of a great “correction” in human population numbers. It will be the result of forces that are inescapable by both man and nature: this will make it a perfectly natural disaster.

What may be scariest of all to me is the thought that the disaster community is mostly silent on issues of overpopulation and over-consumption simply because it is something we may be unwilling or unable to stop.

Catastrophe and Social Change, and the Pre-History of Disaster Studies and Sciences

This monograph is frequently identified as the first sociological, or social science, investigation of a disaster. That does not make it the first disaster-related investigation…the distinction is important. More importantly, as a “scientific” study of a disaster, how good is it? ….you should decide for yourself. Click to view the entire monograph on the National Archives website.

You have probably never heard of this book, published in 1918…neither had I until last night….Prince cites it in his 1920 work.

Ever heard of this article published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, also in 1918, detailing the epidemiology and treatment of eye injuries in Halifax?….

Last night I went to the UT Dallas library to retrieve more Web of Knowledge/Web of Science (WoK/WoS) records. Returning from the Hazards Workshop, I decided it was time to acquire more data, including all Earthquake Spectra articles in WoS (2003 to the present); articles that cite At Risk, Disasters by Design, and several other papers; and to perform a general search for articles prior to 1994 . For retrieving the pre-1994 articles I decided to search for all articles in WoS with either disaster or natural hazard in the topic, published between 1900 and 1994. This produced approximately 6500 records, of which about 6400 are not duplicates of records I already have. Some of these will ultimately be found to be unrelated to disaster studies and sciences, which will likely result in perhaps 6200 new articles covering the formative years of the field.

I was rather surprised by the relatively large number of records found for the first half of the 20th century. The oldest article retrieved with an identified author dates to 1903 (there were several others with anonymous authors, but I did not download these). Even more surprising is the variety of fields contributing to the pre-1960 literature: Sociology, Social Work, Geography, Industrial Chemistry, Occupational Safety, Medicine, Nursing, Public Health, Psychiatry/Psychology, and Law. In reading many accounts of the development of disaster studies, little mention is made to the existence of works pre-Prince (a notable exception is Dyne’s 2000 article concerning Voltaire, Rousseau, and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake-he considers Rousseau to offer the first social science view of disasters) or post-Prince until the 1950s. As research works, it is likely many of these early works lack scientific or methodological rigor. But then again, Prince’s 1920 work, by today’s standard, lacks scientific and academic rigor. He fits his observations into the sociological theories of the day, without much concern for hypothesis testing, or even accuracy (he claims that Halifax was the worst disaster to befall a single community in human history; the 1900 Galveston “flood” does not count because the deaths obviously did not come from just a single community). He did make some very good observations, however, for future researchers to investigate.

Much like the more recent literature of disasters, the early years seem presented in such a way that leads someone to think that virtually nobody, save for Sociologists, and perhaps a couple of Geographers or other social scientists, researched disasters. This makes me a little irritable.

But it makes me very irritable to discover that, even in 2013 , sociologists still try to maintain a belief that Sociology (or Social Science, if they are more clever and do not want to appear so blatantly self-serving of their own disciplinary interests), is the exclusive home for the study of disasters (see Lindell’s paper in May’s Current Sociology that defines “Disaster Studies” as the social and behavioral study of disasters: http://csi.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/05/30/0011392113484456.abstract). My own studies show that multiple liberal arts, social science, scientific, and professional disciplines have been a part of the intellectual landscape, growing more inter-connected with time. In Prince’s monograph, his sociological study involved inputs from philosophy, political science, psychology, and sociology. It does not appear that in his day, disciplinary boundaries were as rigid as they have become today.

There is a harsh possible reality disaster sociology and geography might not want to consider: their way has failed. In the fifty-plus years that they have, by their own admission, held the driver’s seat and positioned themselves as standard-bearers for the study of disasters, relatively little has been accomplished. The field still lacks a widely accepted definition or conceptualization of disasters (Quarantelli, however, has not let this small detail stop him from from advancing the argument that catastrophes are distinct from disasters….). Despite all of the research, all of the the conferences, and all of the rhetoric; and despite the fact that today we live in a world that understands disaster processes better than ever before in the entirety of human history, we cannot stop the economic and human costs of disaster from rising around the world. Their way and their answers have not worked. Trying the same thing again and again, thinking that just a little more effort is all that is needed, will not make a flawed approach work.

Something new is needed.

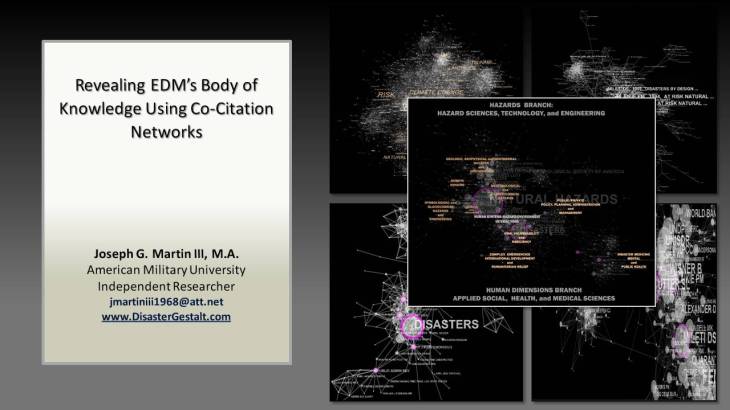

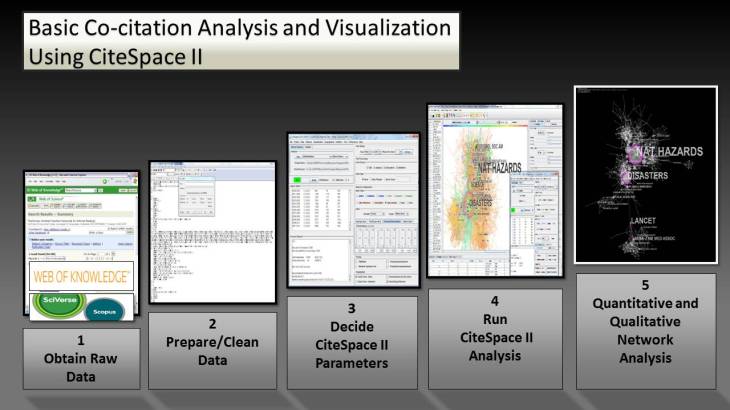

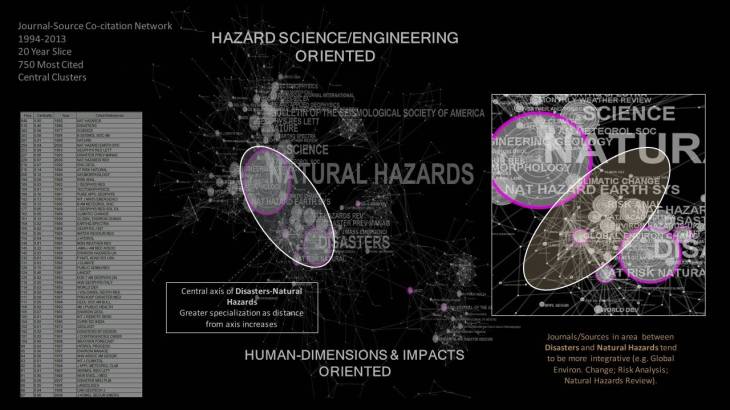

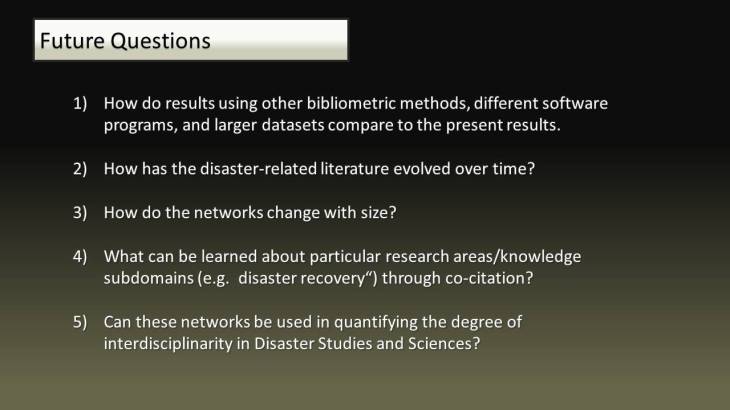

Power Point Presentation Added

The presentation that I had originally planned for the Natural Hazards Workshop was quite a bit longer and more detailed than I actually used based on the time limits given and the strong discouragement repeatedly given concerning use of PP slides at the Workshop. Some of these slides were eventually added to a supplemental handout, and others were dropped.

The full version with all slides has now been given a couple of pages of their own. You can see them here.

Couple of Thoughts on the Relationship of Crises and Disasters

Just wanted to write down some thoughts that came to mind today on the relationship between crises and disasters. They may prove useful at some point: Some crises become disasters but not all crises lead to disaster. Disasters may occur in the absence of any preceding crisis. Disasters, however, may provoke crises.

This suggests that whereas disasters are more distinct events in time and space, crises are more like reactionary “critical decision points” in the lifespan of individuals, organizations, and systems. Unlike ordinary decisions, these crisis decisions are forced upon decision-maker(s) by an event (or events) that bring with them the likelihood of significant negative outcomes. The events that provoke crises can occur internally or externally, and they may occur within the context of a larger disaster that impacts an individual, organization, etc. The negative outcomes that may follow the wrong decisions are not simply undesirable, they are extreme loss outcomes that jeopardize functioning and viability. Depending upon the frame of reference, these extreme outcomes may be called a disaster if they occur.

A crisis can be resolved, which in a sense is to say it can be “undone.” But a disaster, once it occurs, cannot be “undone”. Recovery following the disaster is possible, but not making it so that the disaster never happened in the first place. So a crisis’ relation to a disaster is a bit like the genie in a bottle. In a crisis, the bottle is closed but there is a distinct possibility the bottle will open. The goal is to prevent that happening. If a crisis becomes a disaster the bottle has opened and the genie has escaped. One then must hope to survive and manage the consequences.

Or perhaps this analogy also works. In a crisis the individual, organization, etc., as it moves along its evolutionary journey, is brought by a set of events or circumstances, to the edge of a cliff, perhaps to the point of actually beginning to fall off. A variety of decision paths/actions may be available. Can one change direction and avoid the fall and the chasm (avoidance)? Can the fall be avoided and the chasm safely descended and navigated (crisis as challenge and opportunity for growth)? Is the fall unavoidable but its negative effects can be reduced to acceptable levels (containment of consequences)? If there is failure, then the fall will happen, and the main question becomes only whether or not one somehow survives the injuries caused by impact (crisis as precursor to disaster).

Towards a Taxonomy of “Unfortunate Events” Part 1: Lemony Snicket Might Know More Than We Do…

If you have no idea who Lemony Snicket is, your children probably do: he is the author of the classic children’s book series, A Series of Unfortunate Events.

I am beginning to think Lemony might know more about how to define and develop a taxonomy for disasters than we do. I am only slightly joking when I say that. The thoughts expressed in my recent blogs seem to be leading in a particular direction, which I present here in its embryonic stage:

Although there are quite a few papers regarding the utility of disaster taxonomies (including these by Kreps, Drabek, Barton, and Perry) there have been relatively few comprehensive attempts to establish a taxonomy/typology of disasters, or one within which disasters are contained. Those that have been attempted include: AH Barton’s original and revised view of disasters as a form of “collective stress”; CRED’s 2009 category system for natural disasters; and a 2002 higher order taxonomy provided by WG Green and SR McGinnis.

I can think of three possible explanations for why these attempts have been so far unsuccessful. First, the word “disaster” (as well as other words that could be related) is used within a variety of contexts and purposes, and definitions/taxonomies have been unable to fully account for the similarity/differences between these contexts. If someone says that their job interview was “a disaster,” or says a country’s monetary policy led to “an economic disaster”, and we believe these usages are irrelevant to our taxonomy of disaster, we need to account for how these meanings of disaster are an altogether different creature than saying “the town suffered a tornado disaster,” or “The 1977 Tenerife air disaster is still the deadliest in history.”

I think that the first two uses of “disaster” I gave are all too easily dismissed out of fear of the implications if they are somehow linked to other uses. The implications might include undermining preconceptions or disciplinary boundaries. We might accidentally open the door to studying not only economic collapses, but also job interviews gone bad. I think this is rather absurd. There can be relationships between things without the implication you have to include all of them within your discipline’s boundaries: as a I discussed in a previous blog, chemical processes are reducible to the principles of physics but that does not mean that all physicists are chemists and all chemists are physicists. Still, we still need to recognize that relationships exist and account for them. Or it may simply be that such uses are dismissed because the link appears too complex to determine. The third example of “disaster” usage given seems to be what we in Disaster Studies and Sciences would probably like to be the accepted use. The fourth example, although close to the previous one, becomes problematic because inclusion of some aircraft accidents as “disasters” can both challenge definitions based on event size or scale, but also requires that the relationship between “accident” and “disaster” be elaborated. I believe all four usages of “disaster” given are conceptually linked. And the link can be explained.

Secondly, attempts to create classifications have frequently only considered one, two, or three possible dimensions (e.g. size, scope, cause, effects, etc.) rather than first attempting to determine the number of different dimensions, as well as considering the different levels of organization, that could be used as criteria.

Thirdly, analogous reasoning is rarely used to examine other fields and discover if they have found anything similar. In a transdisciplinary field, the ability to identify underlying similarities between disciplinary views may be key.

So let’s look at a common, very simple formulaic expression of what disasters are:

Disaster= Hazard Exposure x Vulnerability

In other words, a disaster is the product of people being exposed to a hazard to which they have vulnerability. If any of the factors is zero then there cannot be a disaster. Makes sense.

Here is another very simple formulaic expression, but this is an explanation of how mental illness develops:

Mental Illness= Predisposition x Stress

Expressed another way this becomes:

Mental Illness= Genetic/Psychosocial/Physical Vulnerabilities x Exposure to Sufficient Stress.

In other words, mental illness is the product of an individual with a variety of vulnerabilities for a particular mental illness encountering a sufficient level of stresses. If the value for either vulnerability or stress is zero, then no mental illness emerges. This makes sense, too. This is known as the diathesis-stress model of mental illness. There is also a variant called the differential susceptibility hypothesis, which includes accounting for individual variations in genetic and stress vulnerability, as well as both positive and negative influences on vulnerability.

Anyone notice similarity? The fact is that many of the terms and models disaster researchers/theorists use, including vulnerability and resiliency, have been used in many fields as concepts to help explain why sometimes bad things happen, sometimes they don’t.

Here is a schematic diagram of the development of Major Depressive Disorder as the result of vulnerability combined with environmental stress. This is in keeping with the diathesis-stress model. (http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/figures/1471-244X-11-205-1-l.jpg)

Let’s take a look at another concept: “fuzzy” sets” and “fuzzy” concepts, the idea of which is contained in the works of several philosophers, logicians, and mathematicians, but was coined in this 1965 paper by Zadeh (recommended reading beyond the second page only if you, unlike me, love mathematical theorems and such…but it appears the concept works whether you understand the math or not). Many words (let’s take a look at some denoting quantity: some, few, couple, several, many, much, bunch, a lot) have imprecise definitions but are still capable of expressing a meaningful idea. A “couple” of bananas is probably less than “a few of them”, which is less than “many bananas.” But how many bananas are in ” a couple”. More than one, probably less than four or five of them, but definitely less than ten of them. Are three bananas a “couple” of them, “a few” of them, or “several” of them? What we have are words that we understand quite well despite the fact that they have imprecise and overlapping meanings. The meanings may also change or be modified by the context of usage. They are fuzzy concepts whose meanings exist within fuzzy sets. They are also rather unique words in that they are subjective yet amazingly capable of accurately communicating a particular state of affairs.

The “fuzzy” set of “cool” temperatures. Many words/concepts in our language are “fuzzy” yet have remarkable ability to still convey useful information.

Could it be that the word “disaster” represents the expression of a fuzzy concept? Might the definition of disasters and related words, as well as the relationships between each other, be better understood as representing a fuzzy set or maybe subset of a larger set? Can this idea also somehow be integrated into the similarities between models of disaster and illness shown just before? What could link words/concepts found in psychology, psychiatry, medicine, mathematics, philosophy, and disaster studies and sciences? It doesn’t seem possible that such apparently dissimilar things might be related. If we think of disasters and related words as a set of things in themselves, it is perhaps impossible. But if we think of them as a subset within a larger, fuzzy set of similar types of things, we might find success. Are there any theories that might allow this?

Systems theory is the only one that comes to my mind.

So I have added to my Kindle and started reading three works on systems theory (Thinking in Systems: A Primer by DH Meadows; An Introduction to General Systems Thinking by GM Weinberg; and Complex Adaptive Systems by SE Page and JH Miller ). This should come as no surprise to those that have read my blog since the beginning, as this seems an inevitable direction to go based on my discovery of complexity science and self-organized criticality (SOC) earlier this year. What follows is based on my limited understandings so far of systems theory…simple I know, but it is a work in progress.

As presented by Meadows, a system is a “set of things- people, cells, molecules, or whatever- interconnected in such a way that they produce their own behavior over time.” Systems are composed of three basic components: elements, interconnections, and a function. There are inputs, outputs, rules, and feedback loops that govern a system’s behavior. Systems may be composed of multiple subsystems, and what is a system and what is subsystem can depend upon the functional level one is looking. Like the image produced by looking in a mirror with a video camera, there are systems within systems, within systems, within systems, reducible almost ad infinitum. The individual human being is a system, but becomes an actor/agent in a subsystem or system at larger orders of organization. Through self-organization, we as individual systems, join together to evolve larger and ever more complex systems and subsystems (social and otherwise) that are organized into units we recognize as families, tribes, clans, neighborhoods, communities, towns, cities, counties, regions, states, nations, etc…..or what we call cultures , societies, and civilizations.

But systems are not limited to the organic. Non-organic systems also exist at different levels that describe atmospheric, oceanic, and geophysical processes on the planet. The interaction and interdependencies of organic and non-organic systems we recognize as ecological systems. Humans can even create non-organic, non-natural systems we call computer systems, which are increasingly becoming part of complex, intelligent systems. At the extreme of interpretations, the entire planet can be conceptualized as one entire self-regulating, complex system, as exemplified by Gaia Theory. Our planet is composed of a seemingly infinite number of interconnected systems and subsystems. Use of systems theory is not new in disasters, as Drabek’s classic 1986 work looks at the effect of disasters on human systems at different levels; and a systems-based explanation of disasters was offered by D Smith in 2005’s What is a Disaster? (which I feel was one of the weakest chapters in the collection, and which doesn’t seem to do justice to the underlying elegance of systems theory).

What could indicate that systems theory might be able to explain why explanations of disasters seem remarkably similar to phenomena observed in other disciplines? Answer: the shared concept of vulnerability.

Wisner, in a 2004 conference paper that discusses the taxonomy of “vulnerability”, describes the core notion of vulnerability in all its varied uses related to climate change and disaster as “potential for disruption or harm.” I wonder if it is better if Wisner’s idea is changed slightly to say “potential to be disrupted and/or harmed” so that it is clear that we are speaking of vulnerability as a quality of the vulnerable, not of the things that harm and/or disrupt? I wonder this because the concept of vulnerability can apply equally well to the things potentially harmed as it does to many things that potentially harm. As an example, we are vulnerable to many viruses, but viruses themselves are then vulnerable to specific environments and medications. Vulnerability to a threat can be dealt with by employing one or both of two strategies: reduce vulnerabilities/increase resistances to a threat; eliminate/weaken the threat by exploiting its own vulnerabilities. Returning to the example of viruses, these two strategies can be seen in humankind’s ongoing dance with harmful viruses and their inherent ability to reduce their vulnerability through constant mutation.

So perhaps, taking Wisner’s core idea of “vulnerability” as applied to disasters, and looking at its use in other fields, we see the same general meaning: it generally involves something being harmed or disrupted by something else that is capable of causing harm and/or disruption (which I will reduce to just saying “harm”). The things that are capable of harming would belong to a broad class of things we could call, using Latin, nocigenic, or having potential to cause harm. We might also consider it the class of dangerous things. Some of these things might include tornadoes, hurricanes, global warming, volcanoes, fire, certain viruses and bacteria, nuclear weapons, serial killers, suicide bombers, mother-in-laws (ok, so maybe not mother-in-laws)…things that we might call “hazards” or “threats”. However, not all nocigenic things are equal in risk of harm (frequent to extremely rare), or in the scale/scope of harm (individual/specific/local to broad/global), or in the intensity/level (mild/weak to severe/strong/absolute) of harm they could cause. Even though there are differences between these agents, the potential to harm is intrinsic to that which is nocigenic.

Yes, this means that disasters are not simply social in nature or cause, and are more than just a form of “non-routine social problem”, as stated in 1996 by Kreps and Drabek. Proving such statements by arguing that disasters cannot occur without the presence of human civilization, which seems to have almost become a cliche, ignores the equal truth that disasters cannot exist without a nocigenic agent/input acting upon a system. It takes two to tango. Like many sociologists, the definition also takes for granted that “disaster” can only refer to events at higher levels of social organization, without necessarily providing evidence in support (which appears to me to be more of an attempt to make reality conform to a disciplinary demand rather than making the discipline explain what exists in reality).

Meadows also makes an important observation: there are limits to the resilience of systems and their elements. If true, then no amount of social engineering will eliminate disaster events. Nocigenic things that become the agents of “disaster” may trigger the release of underlying social tensions, and the impacts of the agent may be modified by social forces. But a Manhattan-size asteroid about to strike the planet, or the Earth passing into the path of an incoming gamma ray burst from deep space, would be an event that is a non-routine survival problem, regardless of the systems and structures that exist. At a lesser scale, many nocigenic agents at their highest intensities (e.g. 8.0+ earthquakes; category 5 hurricanes; EF4+ tornadoes; super volcanoes; tsunamis; nuclear weapons) have a high propensity for overcoming even the most effectively designed system resilience to produce a result we will still likely call a disaster, though it may be a lesser disaster.

It is unlikely that we will encounter an earth-cooking gamma ray burst anytime soon: estimated probability is around once every 15 billion years (universe is around 13.7 billion years old and earth has been around a mere 6 billion years)…if one did happen would we consider it a “non-routine social problem”? (image from Space.com)

Where this is leading is to the idea that the key to creating a taxonomy/typology of disasters is to recognize that it is one member within a “fuzzy” subset of words that exists within a larger, and equally “fuzzy”, set of words used to describe the adverse, harmful, and disruptive results/outcomes of the nocigenic reacting with the vulnerable. The vulnerable can exist at all levels of system organization, and we can speak of a system as vulnerable, a subsytem as vulnerable, or a system element as vulnerable.

Human beings, however, do have one key feature that must be kept in mind when looking at human systems and larger organizational levels: each individual person (or organizational element within a system or subsystem) has the capacity for independent decision-making and action, including those outside of the rules/parameters of the larger systems of which they are part (a rogue agent, who intentionally or unintentionally, works towards a goal contrary to that of the system) and these actions have the capacity to influence the decisions and actions of those that are interconnected. This fact, combined with the notion that “disaster” is part of a larger fuzzy set that attempts to describe the effects of the nocigenic upon vulnerable things (or to borrow from Mr. Snicket, events that are members of the rather large class of unfortunate events), is what may allow a fuller presentation of what a disaster is, and how the micro-scale and macro-scale is connected.

In Part II, I will present “disaster” as a form of system perception/attribution, made within the frame of reference of the attributor, at various system levels (from the individual to the elements of social systems to the very systems themselves). As such, there can never be one agreed definition, for each attributor can have a different range of events to which they will apply that, or other terms. However, as part of a fuzzy set, there will be a range of events/characteristics to which “disaster” and other words are most frequently applied (for example, we might find that most people will not classify war as a “disaster”, but many may call the unintentional sinking of a civilian ship during war that results in substantial loss of life, a “disaster”; and many might consider global nuclear war a form of catastrophe or cataclysm) . Understanding this may help us to discover something about the complex matrix of characteristics responsible for an event being classified or not being classified a form of “disaster.”

Disasters, Social Construction of Reality, Kant, Hawking, Fractals, and Model-Dependent Reality…

The basic concept of fractals visually explained. Could the idea of fractals help provide a way to reconcile a definition of disasters with issues such as scale (the individual versus the micro-macro scales of sociological organization) and the distinction between the objective and the subjective? Hmmmmm….

Image from http://mathworld.wolfram.com/images/eps-gif/Fractal1_1000.gif

I have been feeling in a philosophical mood this week, so please forgive me if today’s post is not your particular cup of disaster tea.

It has been said that disasters are socially constructed events, and that reality itself is socially constructed.

Interestingly, those who have said this just happen to be Sociologists. Mere coincidence? Or is it possible that disasters are socially constructed events, and that reality is socially constructed…..by Sociologists?

Of course, my tongue is planted firmly in my cheek when I say this. Well, mostly. Disciplinary perspectives are like lenses through which the world can be viewed. Even when the view provided is very useful, it can be easy to mistake that lens as the only useful lens, and that view as the only useful view possible. This is particularly true when looking at complex, multidisciplinary phenomena like disasters. So I do actually get an uneasy feeling when a statement comes from any single discipline that might appear at first blush to not only be making a claim to being the most appropriate discipline for the study of disasters, but to also be making epistemological and metaphysical claims regarding the nature of knowledge and reality. What makes me uneasy is the feeling that a “one lens” view is being offered for phenomena, and a world, that cannot be wholly captured through any single lens, or it can only be captured if you are sure you are using the correct lens. And when the word “reality” enters the picture, there is one very important lens that cannot be ignored.

If this were your house, the standard sociological view is that this is not a disaster. Sociologists, however, would probably agree that it does suck to be you….

Immanuel Kant is probably the Greatest Philosopher Most People Have Never Read. Even one of his most important works, the Critique of Pure Reason, has probably not been read by the majority of philosophy students (and yes I have to raise my hand here). But my tongue is not in cheek when I say that within Philosophy, particularly the Philosophy of Knowledge (Epistemology), it is common to speak of two time periods: the time before Kant and the time after Kant. Any attempts to make claims about what one can or cannot know about the world, or about “reality” must confront Kant. This is because of the Critique. Although it is really more correct to say it is because of a book called the Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysic. You see, Kant’s Critique is, even by the standards of philosophy, one of the densest and most difficult books in philosophy to read. Even philosophers of his own time had difficulty with the 500+ page tome. So Kant wrote Prolegomena more or less as a summary of what he had written in the Critique. And what he wrote usually doesn’t make people feel all warm and fuzzy inside.

Kant came to the conclusion that there is an external world (i.e. the noumenal world; the world of “things in themselves”; the world that can be known without the senses). This world comes to us through our senses and our mind, where it is perceived as the phenomenal world. But our mind is innately designed (one may also say hard-wired) to organize what is sensed according to certain conceptual filters, or what Kant called the Categories of the Mind: Quality, Quantity, Relation, and Modality. We cannot remove these filters. They come with our brain. We can only see the world as filtered through these categories. Thus, even though there is a “real” world external to us, knowledge of it is impossible. I can imagine what it would be like to see the world as my cat Andromeda, but I cannot know what it is like. More importantly: even if by magic I could spend five minutes as Andromeda, the moment I became human again I would still not know, and I probably would not even remember what happened; or what I had experienced would now be incomprehensible and inexpressible as knowledge. You can know the “reality” experienced by a cat only as long as you have a cat’s brain, or only to the extent that a cat’s brain processes the world the same as our own. This is similar to a neuropsychological explanation I read years ago of why we cannot remember our lives prior to the age when we first learned language (first year or two). Once language is acquired, the brain forever changes how memories are encoded and retrieved. Even though the pre-language memories may still be there, our brains no longer have the key to unlock them.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) It is really saying something when you are a philosopher and you write something that even other philosophers have trouble understanding….

Stephen Hawking (1942- present ) Somehow he manages to make the complexities of cosmology and quantum physics understandable. If Kant had been a theoretical physicist, other physicists would still be trying to figure out what he meant….

This is my cat Andromeda (visiting with a friend). Although I cannot “know” , I do have a strong feeling she is more interested in the mystery of how cans of cat food are opened than she is in Kant or Hawking…..

I was reminded of these issues the other night as I was wrote my last post. While writing, I was watching/listening/recording episodes of Stephen Hawking’s Grand Design on Discovery Science. Hawking makes a very basic, and I think, very valid claim: everything within the universe, from black holes to the firing of neurons within our brains, operates within the rules of physics for this universe. Physics is the foundation science of everything, and everything in the universe: chemistry…biology….astronomy….neurology…psychology…sociology…. could be reduced to the principles and equations of Physics. It may be the one disciplinary lens that could be used to accurately describe everything. Of course, although it is logically possible, it is practically impossible, or not very useful to do so. The same holds true when looking at the usefulness of seeing the world solely through the lenses of other disciplines. The lenses of chemistry and biology, for example, are very useful for a wide variety of phenomena, issues, and problems, even if we were capable of seeing everything through the lens of physics. Psychology has been greatly informed by the application of the lenses of chemistry and biology, but those lenses are not particularly useful for seeing all of Psychology, even though it is logically possible to do so. A psychologist can accept the idea of ultimate biological reductionism to all human behavior without having to accept that all problems are best explained and should be treated by pharmacological, medical, or biological means. And this brings me to the relationship between Psychology and Sociology.